The Unnamed Feelings: Reading to understand the indescribable

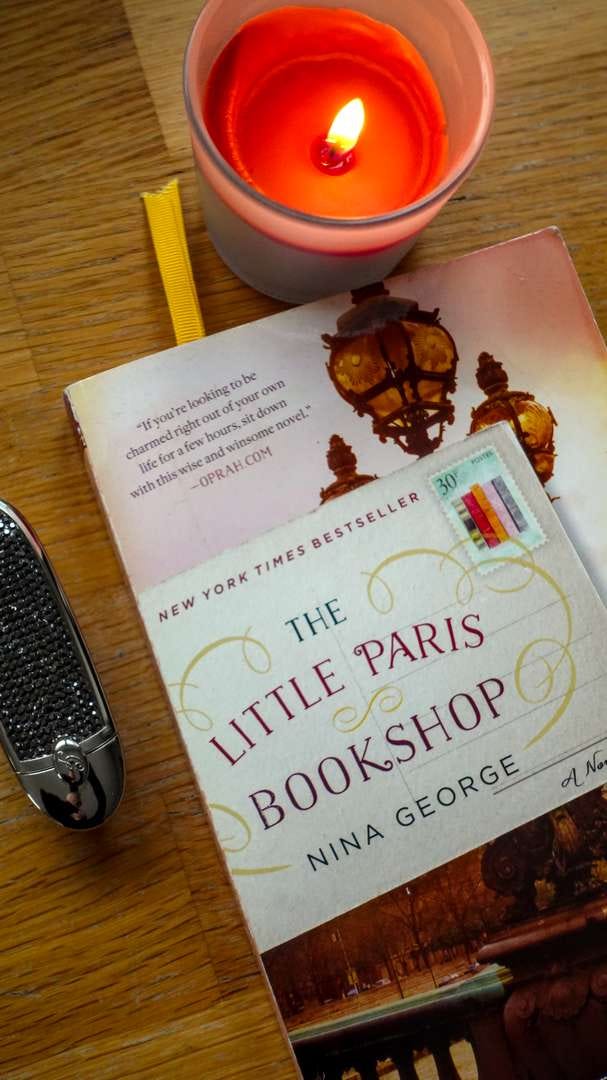

Reflections on The Little Paris Bookshop by Nina George

“I wanted to treat feelings that are not recognized as afflictions and are never diagnosed by doctors. All those little feelings and emotions no therapist is interested in, because they are apparently too minor and intangible. The feeling that washes over you when another summer nears its end. Or when you recognize that you haven’t got your whole life left to find out where you belong. Or the slight sense of grief when a friendship doesn’t develop as you thought, and you have to continue your search for a lifelong companion. Or those birthday morning blues. Nostalgia for the air of your childhood. Things like that.”

― Nina George, The Little Paris Bookshop

There’s a feeling you get in late August. Not sadness exactly. Not depression. Just this low hum of something ending that you can’t name. You’re not crying about it. You’re not calling anyone to talk through it. You just feel it, faintly, like background noise you’ve learned to live with.

And if you tried to explain it to someone, you’d sound ridiculous. “I’m sad that summer’s almost over.” So what? Seasons change. That’s how time works. Get over it.

But Nina George gets it. She has a character in The Little Paris Bookshop talk about treating feelings that have no diagnosis. The ones doctors don’t recognize. The ones therapists wave away because they’re too small, too intangible, too minor to count as real problems. And that her character, Monsieur Perdu, treats by prescribing books.

Those feelings. The ones you carry quietly because you’re not sure they’re valid enough to voice.

What Literature Names That We Cannot

There are emotional states that exist in the space between fine and not fine. States we experience regularly but have no language for.

The hollow feeling of walking through your childhood neighborhood as an adult. The specific anxiety of realizing you’ve become boring to someone who used to find you fascinating. The weight of a Sunday evening when you’ve done everything you were supposed to do but still feel like you wasted the weekend. The quiet panic of being exactly where you planned to be and wondering if you planned wrong.

These aren’t traumas. They’re not clinical depression or diagnosable anxiety. They’re just the small griefs of being alive and paying attention.

And we don’t talk about them because they seem too trivial. Because saying them out loud feels like making a big deal out of nothing. Because we’re supposed to be resilient enough to handle a neighborhood that’s changed or a Sunday that felt empty.

But then you read a novel and someone describes exactly that feeling. Not explaining it. Not analyzing it. Just acknowledging that it exists. That it has texture and weight. That you’re not inventing it.

And suddenly you’re not alone with it anymore.

The Relief of Recognition

I think this is one of the main reasons we read fiction. Sure, for escapism as well. At times, to learn something. But also to encounter a feeling we’ve had and never known how to name.

You read a character experiencing the birthday morning blues and you think: oh. That’s a thing. That’s not just me being ungrateful or melodramatic. That’s a real emotional state that happens to people.

Literature doesn’t fix these feelings. It doesn’t make the late-August melancholy go away or resolve the disappointment of a friendship that didn’t deepen. It just says: yes, this exists. You’re feeling something real.

That recognition is enough.

Because most of the time, we’re moving too fast to notice these small feelings. Or we notice them and immediately dismiss them as unimportant. We don’t give them language because language makes things real, and these feelings seem too minor to deserve that kind of attention.

But fiction slows you down. It lingers on a character’s interior landscape long enough for you to recognize your own. It gives form to formless things. It treats minor feelings as worthy of description.

The Things We Don’t Say Out Loud

There’s something about reading that lets you acknowledge feelings you’d never voice in conversation.

If a friend asked how you were doing, you wouldn’t say “I’m experiencing a slight sense of grief because a friendship didn’t develop as I thought it would.” You’d say “I’m fine” or maybe “I’m a little tired.” Because the real answer sounds too complicated. Too needy. Too much like you’re making problems where none exist.

But when you read about that same feeling in a novel, you don’t have to justify it. You don’t have to explain why something so minor affects you. You just get to feel it alongside a character who’s feeling it too.

Literature creates permission. It says these small, unnamed feelings are part of the human experience. Not symptoms to fix. Not problems to solve. Just states we move through. States that deserve acknowledgment even if they don’t deserve intervention.

Why the Small Feelings Matter

I don’t think these feelings are actually minor. I think we call them minor because we don’t have a framework for understanding them.

We have language for big emotions. Grief. Joy. Rage. Love. We know what those are. We know they matter. We give people space to feel them.

But the feeling that washes over you when summer ends? The nostalgia for childhood air? The quiet recognition that time is limited and you still haven’t found where you belong? Those don’t fit into our emotional vocabulary. So we minimize them. We treat them as background noise instead of legitimate experiences.

But they shape us. They accumulate. They’re the texture of daily life, the undertone of existence. And when we read about them, when a novelist takes the time to describe them with care and specificity, we realize they’ve been there all along. We’ve just been pretending they don’t count.

Reading as Recognition

This is what I come back to over and over. Reading isn’t about escaping your feelings or understanding them or fixing them. It’s about recognizing them.

You read a passage like Nina George’s and you think: someone else knows about this. Someone else has felt this too. Someone thought it was important enough to write down.

And in that moment, you’re a little less alone with the unnamed thing you’ve been carrying. You have language for it now, even if the language is borrowed. You have proof that it’s real, that it happens to other people, that it’s worth noticing.

That’s the ritual. Not looking for answers. Not searching for meaning. Just encountering your own interior life reflected back at you from the page. Just reading until you find the feeling you couldn’t name. Just sitting with the relief of knowing: this exists. You’re not making it up.

The birthday morning blues. The late-August hum. The slight grief of a friendship that didn’t become what you needed. The nostalgia for air you’ll never breathe again.

Things like that.

All the little feelings no one talks about because they seem too minor to matter. Until you read about them. And then they matter more than you thought possible.

This reflection grew out of my recent reading of The Little Paris Bookshop, which I wrote about in my November Mood Board. If you’re curious about what else I’ve been reading at the beginning of this month—the books that are shaping how I think about autumn, transitions, and the quiet weight of everyday life—you can find it on the main site: November Mood Board.